My Unfiltered Take on the AI Coding Agent Landscape

(Translated from my Chinese post by Gemini)

Agentic coding is arguably the hottest (and most hyper-competitive) space in tech right now, with a thousand companies jumping into the fray. Every other day, social media is flooded with announcements of a new tool or a new feature, each claiming to be mind-blowing or revolutionary. It's dizzying, and I see a lot of people asking, "Are these AI coding tools really that good?" or "What's the actual difference between X and Y?" Many try them out, feel underwhelmed, and quickly lose interest. At the same time, I'm surprised by how many programmers haven't even used Cursor.

As someone who loves tinkering with all sorts of agentic coding tools, I can't resist sharing my sharp take. While the field is undoubtedly saturated with hype, if you look closely, you can discern the real differences between products and even map out the trajectory of the entire industry.

There's a significant element of "art" or "craft" in understanding what an agent can and cannot do, and how to use it effectively. This makes it hard to explain. The best way to truly get it is to try them yourself. No amount of reading other people's reviews can replace hands-on experience (but here I am, unable to resist sharing my thoughts anyway). This article is my attempt to organize my scattered observations and thoughts on various AI coding tools into a coherent piece.

Some Background

Broadly speaking, I'm a firm believer in the future of "agentic coding." To be more specific, I believe that AI agents will eventually be able to independently handle complex, end-to-end development tasks (adding features, fixing bugs, refactoring) within large-scale projects.

For context, my day job involves writing code for RisingWave, an open-source streaming database. It's a fairly complex Rust project with over 600,000 lines of code. While I've grown accustomed to letting AI handle small, well-defined tasks, I'll be honest: I haven't yet seriously used AI coding for the truly difficult development work on a large scale. I also haven't deeply pondered the ultimate capability boundaries of future models or the specific technical hurdles in building agents. So, this article is mostly based on my intuition—a qualitative analysis of various tools, not a "how-to" guide or a product comparison.

But to make an excuse for myself, I think there's a reason for my hesitation, and it mostly boils down to a "scarcity mindset": Agents are still too expensive! A single task can easily burn through \$5 to \$10. This might be a case of the Jevons paradox: if they became cheaper, I'd use them more and end up spending even more money… Another issue is the sheer number of tools. To truly appreciate the differences, you'd need to spend a week or more with each one, but the cost of subscriptions and the friction of switching are daunting.

With that out of the way, let's dive in. We'll analyze the tools one by one, and then discuss some broader topics.

Specific Product Analysis

Cursor: The Ambitious Frontrunner

Cursor is, without a doubt, the big brother in the AI Code Editor race.

Clues Hidden in Versions 0.50/1.0

A major trigger for writing this was reading Cursor's 0.50 changelog (though by the time I'm finishing this, they've already released 1.0…). It revealed some fascinating hints about their future direction:

-

Simpler, unified pricing: Cursor's old pricing model was a bit notorious, introducing a vaguely defined "fast request" with different quotas for different models. The new version unifies this into "Requests" (though it's not a huge change). More importantly, while many find \$20/month expensive, I think it's priced too low; they're likely losing money. Per-request billing is inherently problematic, especially in the agent era where a single request can run for a long time and consume a massive number of tokens. Of course, this could be a "gym membership model," where low-usage or short-conversation users subsidize the high-usage ones. But another issue is that it incentivizes them to optimize for token cost (e.g., by compressing context), whereas users want maximum performance.

-

Max mode: According to the official description, "It's ideal for your hardest problems." In my opinion, that's a bit of an overstatement. My understanding is that Max mode simply stops micromanaging context and introduces token-based billing. In the past, when models had weaker long-context capabilities, fine-tuning the context might have saved money and improved results (as models could be misled by irrelevant information). But now, with models improving so rapidly, this control has become a negative optimization. It's interesting that open-source BYOK solutions like Roo Code have always advertised "Include full context for max performance." So, Cursor's move feels like a step backward, or perhaps an early optimization that has now become technical debt. Their line, "If you've used any CLI-based coding tool, Max mode will feel like that - but right in Cursor," feels even more subtle. If I can use a CLI-based agent, why would I use a version in Cursor that charges an extra 20% margin?

-

Fast edits for long files with Agent: This also feels like a regression. It suggests they are starting to use text-based methods to directly apply the model's output. Cursor used to boast about its sophisticated

applymodel, but perhaps they built it too early. When models were less accurate, complex application logic was necessary; as models get stronger, that complexity may become redundant. -

Background Agent & BugBot: In general, the "Agent mode" is more like assisted driving. A true Agent is something you can delegate tasks to more effortlessly. The Background Agent lets you fire and forget, while BugBot provides automated code reviews. Inevitably, they will add features like assigning a GitHub issue to the agent to have it start working, turning it into an all-purpose workhorse.

The signal is crystal clear: Cursor is going head-to-head with Devin. This is a natural progression. Anyone who has used Cursor's agent mode has probably thought, "Can I make it do two things at once?" Doing this locally is difficult, but moving it to the cloud makes it a logical next step.

Cursor vs. Devin is a bit like Tesla vs. Waymo. Waymo aimed for the ultimate goal of full self-driving from day one. Tesla, on the other hand, built a mature product with a large user base and then gradually moved towards more automation. The advantage of Tesla's path is that user expectations are lower. If something goes wrong, the human can take over. They can also maintain user stickiness by leveraging other well-executed features. In contrast, if Devin's initial experience doesn't meet expectations, users might churn immediately. (Of course, for pro users, checking out and modifying code locally is trivial, but Cursor has a large base of less-technical users, and providing a simple UI/UX for them is a key selling point.)

-

Other small improvements in 1.0:

- Support for memory: I believe this is a must-have for any AI agent.

- Richer Chat responses: Support for Mermaid diagrams and Markdown table rendering. This shows there's still room to compete on the chat experience (to boost user stickiness).

- Overall, though, 1.0 feels more like a marketing-driven release without any qualitative leaps (compared to 0.50, which was more shocking to me).

Corresponding to Cursor's aggressive moves is the news that Anysphere, which makes Cursor, has reportedly raised \$900M at a \$9B valuation. Paired with OpenAI's rumored acquisition of Windsurf, it's clear Cursor has ambitions to dominate the market. With so much funding, I suspect their next move might be to train their own models. They could also very well acquire other players in the market and become an consolidator.

So, what makes Cursor so good anyway?

Looking back, the reason I started using Cursor (around May 2024) was for its stunning TAB feature. In the early days, I barely used AI chat and was willing to tolerate many annoying editor bugs just for this. Compared to GitHub Copilot's "append-only" completions, where you have to delete and retry to make a change, Cursor's generative "Edit" is clearly the more "correct" approach, and its accuracy is quite impressive. Its completions can also jump ahead and modify multiple places after fixing one, which is incredibly useful for refactoring. For example, when changing a type signature, an IDE's refactoring might not be smart enough, requiring many manual edits. Cursor solves this pain point.

For this TAB feature alone, I willingly paid my \$20.

Later, almost without me realizing it, "Agent mode" caught fire among non-coders. It was only then that I belatedly discovered the power of agents. (And Cursor never raised its price! Which is why they are now gradually acclimating users to token-based billing.) I'm not sure if this explosion in popularity was accidental. In my view, other AI IDEs or end-to-end coding platforms can do similar things, and Cursor is now even a bit behind on the agent front. But perhaps because they were early, they seized a window of opportunity and successfully established their brand in the public consciousness. The switching cost for AI coding platforms is a bit of a mystery. On one hand, it's not hard to switch if you really want to; there's no qualitative chasm in experience, no real moat. On the other hand, once you get comfortable with a tool for your daily work, you're reluctant to change.

They have a post, Our Problems, where the vision they laid out was mostly in the realm of AI-assisted coding. Now, in the age of agents, it feels a bit dated. There's still a lot that can be done for the UX of AI-assisted coding, but with the heavy focus on Agents, it might not be a top priority anymore.

So, what makes Cursor good? It's a strange combination of punches. They first captured the most discerning core users with a killer feature that truly understands developers (that unbeatable TAB Edit). Then, they astutely caught the Agent wave, successfully equating their brand with the concept of "AI programming" in the public mind, even if their technology is not the most advanced today. This blend of hardcore capabilities and a knack for catching trends, combined with a bit of first-mover "magic," has cemented their current position.

If you're unsure which tool is right for you, Cursor is probably a safe bet: well-funded, maybe not the absolute best at everything, but certainly not bad at anything.

What is Cursor's endgame?

Many people used to ask why Cursor forked VS Code to do what it does. I once thought the answer was "an experience specialized for AI" (like the Cursor TAB). But now, with VS Code and Augment Code catching up, Cursor itself hasn't produced more eye-popping, unique UX innovations.

My current judgment is this: Cursor wants to be a comprehensive, all-in-one platform that owns the developer's entry point. (GitHub Copilot might want this too, but it's not moving fast enough.) My earlier point about "I can use an agent in the CLI" implies that agents don't need an IDE to function. But after briefly using Cursor's background Agent, I found the experience very natural. Many things don't have to be in an IDE, but conversely, there's no reason they can't be. Since the IDE is where engineers spend most of their day, why not stuff everything coding-related into it and make it a one-stop hub?

As for other AI code editors (Windsurf/Trae, and open-source ones like Cline/Roo Code), I feel it'll be hard for them to compete with Cursor. My view is that Agents are the macro trend, and once you get Agents right, the reliance on AI-assisted coding diminishes. When engineers need to write code themselves, they'll ultimately return to the traditional IDE experience. While these other tools might have advantages in certain areas (Windsurf is said to have smarter context management for complex projects), the average user doesn't have the patience for deep comparisons. In the face of massive capital, these minor differences will likely be smoothed over or consolidated through acquisitions. And building agents is a cash-burning game. On the other hand, a code editor built from scratch, like Zed, might just be able to pull off something new.

On "Moats"

Cursor's founder once talked about their view on "moats": in a field that's moving this fast with such a vast imaginative space, the only real moat is speed. As long as you're fast enough, you stay ahead. Conversely, no matter how strong your current tech or product experience is, if you slow down at any stage, you risk being overtaken and replaced. It's brutal.

I haven't fully wrapped my head around this. I used to think that "experience" could be a moat. But perhaps that's only when the game you're playing isn't big enough. If it's big enough, the giants will inevitably step in, build it themselves, and outperform you with their technology (models) and resources.

VS Code/GitHub Copilot

Copilot was an absolute milestone, the first AI coding tool that felt "usable." But its experience has since been surpassed by newcomers. My guesses for why this happened include:

- OpenAI/Microsoft's priorities shifted (e.g., Microsoft's big push for Copilot for Office).

- Microsoft is a giant corporation with layers of bureaucracy, and GitHub Copilot might not get enough resources.

- Copilot might have started as an experiment. After its initial success, they might not have had a clear vision for the next steps. Plus, the development of coding-specific models was slow (Codex was a finetune of GPT-3), and the focus shifted to improving base models, leaving no one/no resources to train specialized coding models.

- As Copilot's user base grew (especially enterprise users), making drastic changes to the experience became a burden. Being the market leader became a liability.

- Being constrained by the VS Code shell, unlike a forked AI IDE, they couldn't make radical changes. Pushing AI-related features into the main branch was likely a delicate matter, especially back when AI coding was not yet a consensus and many programmers were hostile towards it.

However, VS Code has been gradually adding these features back. They even published an interesting declaration: VS Code: Open Source AI Editor.

In the long run, VS Code will likely reclaim the throne. The reason is simple: a big company getting serious is a scary thing (see: Gemini). Once AI coding becomes a consensus and Microsoft invests enough resources, the experience gap will likely close (there's no reason Copilot can't build something like Cursor's TAB feature), unless Cursor continuously innovates on "AI Editor UX." But so far, that doesn't seem to be the case. More importantly, since agents can work without an IDE, when programmers write code themselves, they will gravitate back to a traditional IDE that is feature-rich and has fewer bugs. This is a major weakness for Cursor, which always seems to be half a step behind VS Code in its core IDE iteration.

A future where VS Code and Cursor dominate the market, each catering to different tastes—those who prefer the classic and those who want the all-in-one—seems quite plausible.

Claude Code

Next, let's talk about true CLI-based agents.

As I analyzed in a previous post, Claude Code is a very thoughtfully crafted product. It gave me the feeling that "this should actually work" and was the first time I seriously considered that an agent might not need an IDE.

Compared to agents in an IDE or browser, a CLI-based agent isn't fundamentally different; the main distinction probably lies in the design of its prompts and tools. But its advantage is that it can iterate faster. By doing less, it can focus on the essence of what an agent is. As analyzed in my last post, Claude Code's prompts and tool specs are incredibly detailed and long. My personal experience is that Claude Code feels noticeably "smarter" than Cursor. Is this just due to superior prompt engineering? Or does Claude Code have access to a special model? (Doesn't seem like it for now, but who knows about the future.)

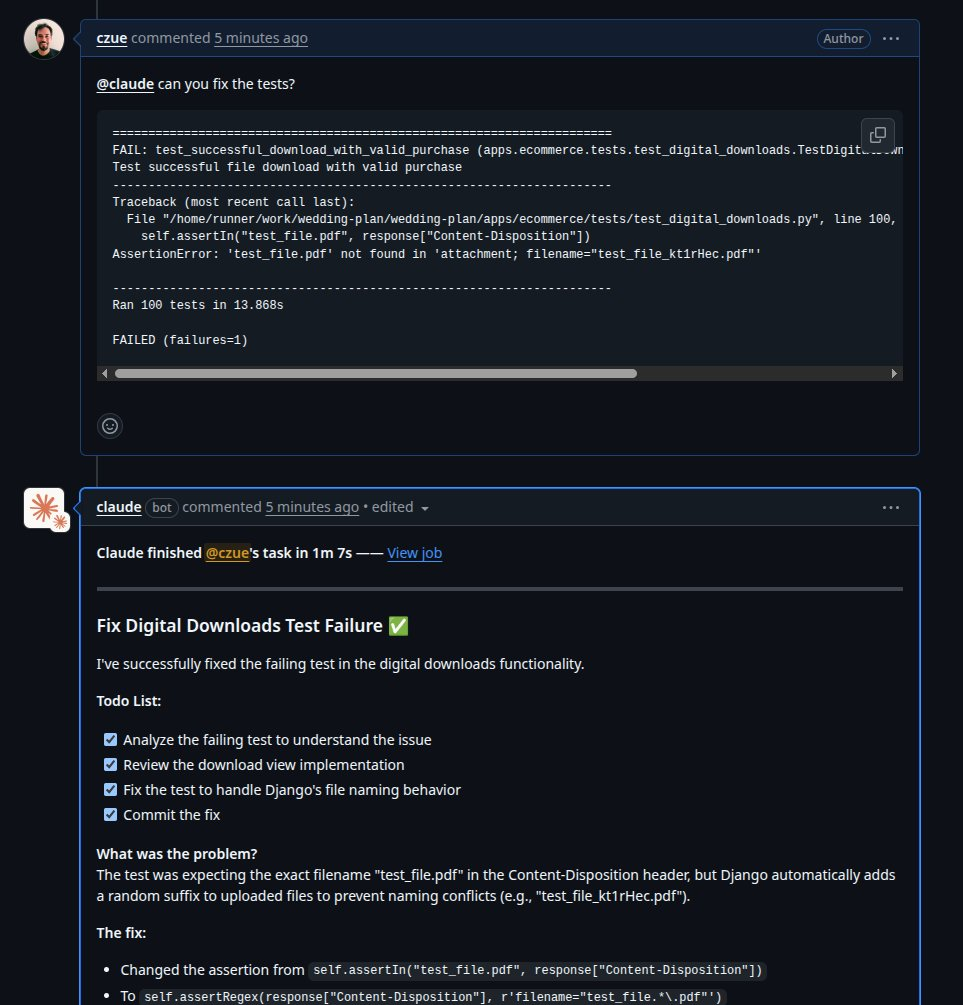

Claude Code isn't confined to your local terminal; you can now @-mention it on GitHub and have it work on its own (running in CI). But its approach isn't deep integration, but rather leveraging the infinite composability of the CLI (a very first-principles way of doing things?).

Over the past month, Anthropic has made more moves that suggest a strong push for Claude Code:

- Announced Claude Code 1.0 and a new 4.0 model at the "Code with Claude" conference.

- Cut off supply to Windsurf.

- Made Claude Code available to Claude Pro subscribers (\$20/month), significantly lowering the barrier to entry.

That last point convinced me to subscribe to the Pro plan. I tried it out. Before hitting my usage limit (which refreshed a few hours later), I had Claude Code run a fairly complex refactoring task that lasted about 30-40 minutes. If billed by API tokens, that usage would have cost at least \$10. This might be a key advantage for an LLM provider building its own agent: the machines are already there, so they can fully utilize idle resources. Application companies, on the other hand, can't afford to lease dedicated machines.

What is Anthropic's real intention with Claude Code?

I haven't fully figured out Anthropic's ultimate goal with Claude Code. Is it to build a great product, or to use it to aid in model training itself? OpenAI is clearly putting effort into ChatGPT as a product, with the future vision of it being a dispatching agent or an entry point. What is Claude Code's role in this picture?

This partly depends on one's judgment of the size of the coding market. Judging by Cursor's initial valuation, the consensus was that it was so-so—the developer population is only so large. But now, with the rise of "Vibe Coders," the narrative has expanded considerably.

Still, for a major model company like Anthropic to jump into the application layer feels a bit… "improper." Perhaps their goal isn't to eat everyone else's lunch, but to experiment and see what this kind of thing can become. But speaking of applications, the Claude App itself has some beautifully designed features, like its Artifacts, which offer a much better experience than ChatGPT's, even if the overall Claude App is clunky.

Of course, the more likely goal is to collect data from user interactions to train their models. They probably can't get user behavior data from partners like Cursor. So they have to build a complete product to close the loop. Moreover, they might not care about all the miscellaneous features in Cursor; their focus is likely on the parts of the training process that are directly related to coding.

The Evolution from "Smart" to "Persistent"

Speaking of model training, Claude Code's claim of being able to run independently for seven hours gives me a feeling: the "intelligence" of models seems to have hit a short-term plateau, so everyone is now focusing on "long-term task execution" (i.e., Agents)—making models work longer, more autonomously, and use tools to augment themselves.

In use, you can clearly observe new behaviors from the model:

- It will first say, "Here's what I'm going to do: 1, 2, 3," demonstrating task planning ability. (I used to think an external to-do list was necessary, but it seems to be internalizing this.)

- It will start writing a solution, then suddenly say, "Let me think if there's a simpler way," and start over.

These behaviors are actually quite amusing to watch, but they clearly show the path towards becoming a true agent.

Amp

My overall impression of Amp is that they have a great "product sense" and "really get how agents should work." But fundamentally, it's Claude Code-like. The advantages I can think of are: they can move (slightly) faster(?); they have Sourcegraph as a backend for code search & indexing (is that really useful?); they aren't tied to Claude, so they can switch when other models catch up. Additionally, their unapologetic, principled product philosophy might win them a deeply loyal user base. Here's what they say:

- Amp is unconstrained in token usage (and therefore cost). Our sole incentive is to make it valuable, not to match the cost of a subscription.

- No model selector, always the best models. You don’t pick models, we do. Instead of offering selectors and checkboxes and building for the lowest common denominator, Amp is built to use the full capabilities of the best models.

- Built to change. Products that are overfit on the capabilities of today’s models will be obsolete in a matter of months.

Their “Frequently Ignored Feedback” page is also fascinating (User: I want X; Amp: No, you don't), showcasing their deep understanding of agents:

- Requiring edit-by-edit approval traps you in a local maximum by impeding the agentic feedback loop. You’re not giving the agent a chance to iterate on its first draft through review, diagnostics, compiler output, and test execution. If you find that the agent rarely produces good enough code on its own, instead of trying to “micro-manage” it, we recommend writing more detailed prompts and improving your

AGENT.mdfiles.- Making the costs salient will make devs use it less than they should. Customers tell us they don’t want their devs worrying about 10 cents here and there. We all know the dev who buys \$5 coffee daily but won’t pay for a tool that improves their productivity.

Very opinionated, with a certain "Apple-esque flavor."

They've also built a leaderboard & share thread feature, which is interesting and could spark some unique dynamics within a team.

However, I'm cautiously pessimistic in the short term. Claude Code is already good enough and has a huge cost advantage by being bundled with a Claude subscription. Amp's current model is a complete pass-through of token costs (no margin). So while they aren't profitable, they might not be burning too much cash either. One to watch.

OpenAI Codex (in ChatGPT)

Last month, OpenAI also released its own fully automatic coding agent. It's exactly the product form I imagined for an agent. I had been wondering why I couldn't assign tasks to Cursor from my phone. Now, I can do it through ChatGPT.

But to understand this move, you can't just look at coding. Although they acquired Windsurf, I believe OpenAI's ambition is far greater than just getting a slice of the coding pie; they want to make ChatGPT the future dispatching hub, or even an operating system. The purpose of Codex might just be to enable more professional, "high-value users" to do more, thereby increasing user stickiness. The Windsurf acquisition was likely for their long-context management capabilities and valuable user data, which can empower model improvements.

On a side note, the overall experience of ChatGPT is far superior to other official AI apps. For instance:

- Memory: It has a magical feel, but for me personally, the "value" it provides isn't that significant yet. For truly personal or reflective questions, I still prefer to ask the memory-less, and even clunkier, Gemini.

- The web search experience in o3 is exceptionally good. It's like a mini DeepResearch.

- While not perfectly smooth and still a bit buggy at times, it's still much better than the competition.

Devin

Back when AI coding wasn't so widespread, they branded themselves as the "First AI Software Engineer," aiming for fully automated, end-to-end development. Their initial price of \$500/month was prohibitive. And those who tried it said it was clumsy.

Now that it starts at \$20 with a pay-as-you-go model, I immediately gave it a try.

My overall impression is that the model's intelligence is so-so. But the product as a whole feels like it "basically works." I have a strong feeling that with proper prompt engineering, it could work very well. Their current messaging is also very realistic: "Treat Devin like a junior engineer." (In fact, this is probably the state of any agent product right now.)

This was my first real taste of how expensive agents can be. I gave it an issue to handle, and it was able to autonomously figure out a framework (costing 2 ACUs, at \$2.25 each). But when I asked it to fix a bug, it struggled, started thrashing, and quickly shot up to 4 ACUs. My \$20 evaporated in no time. Perhaps the best way to use it now is to have it generate a first draft, and then manually refine it or use Cursor. (Of course, now that Cursor has a background agent, the lines are blurring.)

For Devin (and now Cursor's remote agent), there's also the cost of vCPUs. For example, an m5.4xlarge (16C64G) on-demand is \$0.768/h. Compared to token costs, that's actually not that expensive…

With agents becoming a hot topic, Devin is now being squeezed from all sides by Cursor, Claude Code, Codex, and others.

Devin's current advantages lie in its integrations (you can assign tasks directly from Slack, Linear & Jira) and its high product polish (a well-designed knowledge base and playbook system). But can this "dirty work" justify its valuation and become a moat? Intuitively, these seem like features any good agent must have. It feels like the agent space requires a massive amount of time to polish the experience, but the capital seems to be in too much of a hurry.

Their latest Confidence rating feature is excellent, as it can prevent users from burning money on a pile of garbage due to overly high expectations. This is another interesting aspect of agents: if you use them incorrectly, the results will be poor and expensive. To put it another way, a good programmer or contractor doesn't just do what you say; they try to understand your intent, why you want to do it, and what the potential pitfalls are.

Their DeepWiki also feels like a flex, possibly showcasing their technical accumulation in agent technology. After all, they are a team that raised huge funds from the start to self-develop large models, aiming for massive context windows. Perhaps they have a lot of GPUs and a cost advantage.

While writing this, I saw a new platform called Factory, which also seems to be challenging Devin. Its release announcement sounds almost too good to be true: "Factory integrates with your entire engineering system (GitHub, Slack, Linear, Notion, Sentry) and serves that context to your Droids as they autonomously build production-ready software." But upon closer inspection, this company was founded even before Devin. An interesting detail in their demo video is that all integrations redirect you back to their Factory page (e.g., you @-mention it in Slack, and it gives you a link). The experience is that you do everything from their portal, pulling in context from Linear, GitHub, and Slack. (To use an imperfect analogy, it looks a bit like the Manus of the coding world.) In contrast, Devin lets you interact with it directly in Slack and Linear, which is more in-context and in-flow. But anyway, competition is a good thing.

v0

The tools discussed so far are mostly designed for engineers (whether fully or semi-automated). Now let's talk about platforms geared more towards "non-coders" or "product" people.

v0 is a niche within a niche in the coding vertical, focusing on front-end UI prototyping. You can think of it as a Figma driven by natural language, where you can "draw" interfaces directly in v0. Another clever aspect is its use of React/shadcn UI's component-based nature, meaning the generated code can be directly integrated into your own projects, making it actually usable.

Vercel has always been a company with great "taste." Leveraging their deep expertise in the front-end world, they've made the experience of this niche product, v0, excellent. But one can imagine that behind v0's smooth experience lies a ton of engineering optimization, such as using templates, specially fine-tuned models, and a meticulously designed workflow to ensure quality output.

An interesting development is their recent release of their own model family and opening up its API. Their explanation is: "Frontier models also have little reason to focus on goals unique to building web applications like fixing errors automatically or editing code quickly. You end up needing to prompt them through every change, even for small corrections." This is very reasonable, but is it just polishing the details? Of course, to deliver a usable product, such polishing is essential. But I don't quite understand why they released an API. Perhaps it's to recoup the cost of model training on one hand, and on the other, to start exploring how to become a "dispatchable agent" themselves.

But it feels like they aren't content with just doing UI. Their positioning is now a "Full stack vibe coding platform." They are also working on GitHub sync and other integrations with existing codebases, moving beyond just generating things on the v0 platform.

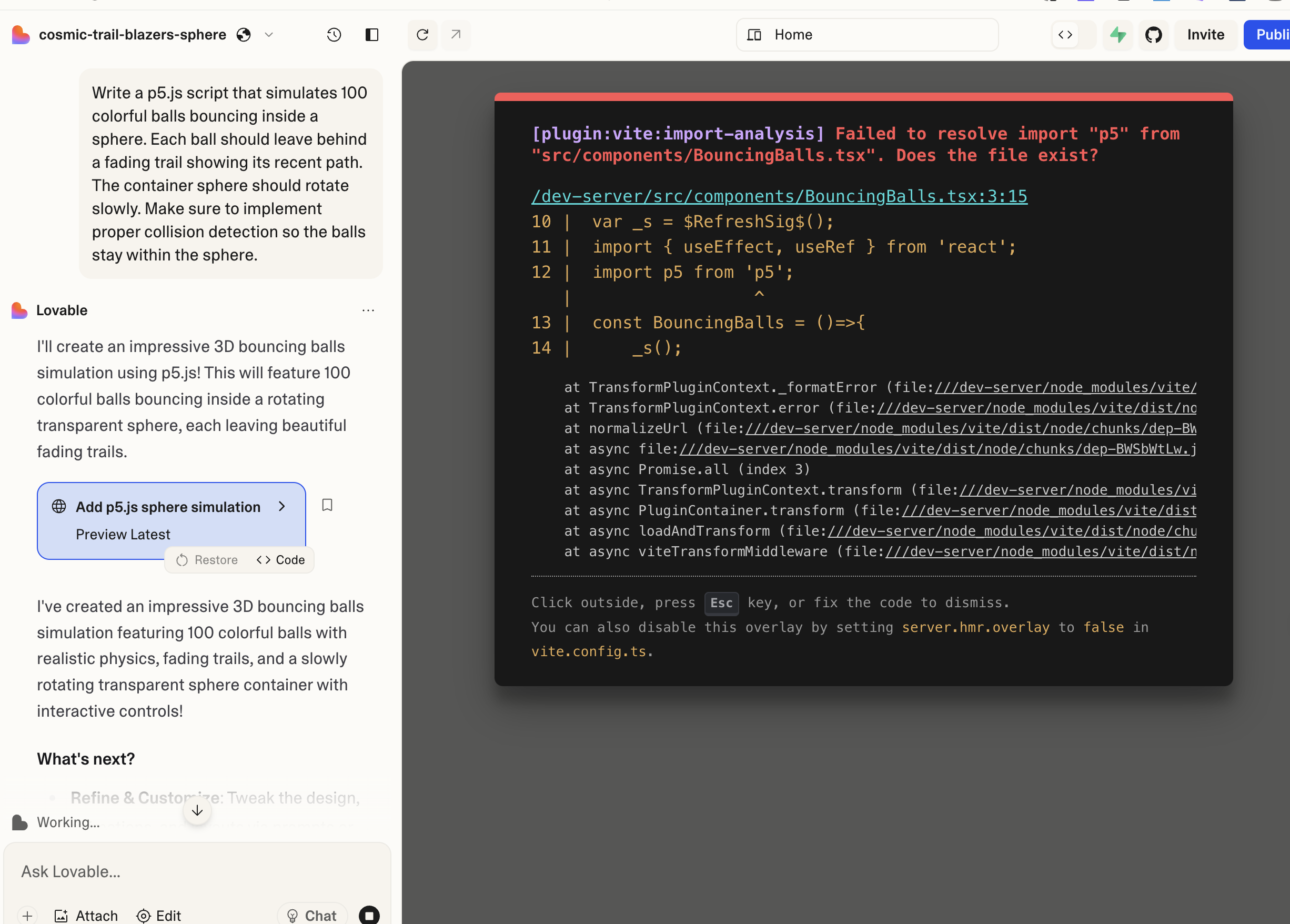

Bolt / Replit / Lovable: "Idea to App" Vibe Coding Platforms

These types of products are, to some extent, variations on a theme. They are all end-to-end, full-stack platforms, or app builders, with a catchier name: "idea to app" platforms.

Compared to Cursor, the pain points they solve are deployment (including front-end, back-end, and database) and a smoother "vibe coding" experience. The thinking is: if I'm not going to look at the code generated in Cursor anyway, why even show me a code diff? A chat-to-live-preview experience is more direct. They also likely use project templates to make the initial "prompt to app" experience feel amazing.

While their target audiences might differ slightly—perhaps developers prefer Bolt, and non-developers prefer Lovable (pure speculation)—they are essentially doing the same thing: enabling users to build a usable product with close to zero manual coding.

The Dilemma of Vibe Coding Platforms

The tricky part is that if their goal is to deliver a final product to the user, user expectations will be very high. In serious scenarios, users often need very specific modifications, and letting an AI handle everything might not achieve the desired result, not to mention it's expensive. When I was using Cursor to whip up a front-end, adding features was a breeze, but when I wanted to fine-tune a button's position, layout, or interaction logic, it often got it wrong.

Although some vibe coding platforms offer an online code editor, when it comes to fine-grained control, people who can code will likely go back to Cursor, because it's the most comfortable tool for the job. But once they're back in Cursor, there might be no reason to return to the vibe coding platform. The pain of deployment is a one-time thing; once CI/CD is set up, you just push your code changes.

For detailed development, Cursor's agent can probably provide more precise context. These vibe coding platforms could also enhance their own coding agent capabilities, but they have too much on their plate. Building out a full platform takes a lot of effort, and their technical accumulation in coding is surely no match for developer-focused platforms like Cursor.

In short, the ceiling for vibe coding platforms in serious, complex scenarios might be limited. They certainly have value for simple projects or demos, but how many users are willing to pay for that, I don't know. This story has already played out with PaaS platforms like Vercel/Neon that focus on "developer experience": everyone praises the experience, but once projects get large, many quietly migrate to AWS.

Looking at it from another angle, let me make a bold prediction: in the future, Cursor could very well build out a great vibe coding / app builder experience. They could make the initial screen a chat box, integrate live previews, and add Supabase/Vercel integrations. If that happens, these other platforms will be in even greater danger. After all, the concept of "vibe coding" originally took off on Cursor, and for people who want to build products, "seeing the code" might not be that big of a hurdle. I boldly predict Cursor might do this within a year.

Let's also look at Lovable's FAQ where they compare themselves to other platforms/Cursor:

- Most of the points are vague claims like "just better," "way more natural," "Attention to detail." This might be convincing for a regular product, but in the hyper-competitive AI coding space, it's incredibly hard to stay ahead.

- They have a visual editor, which is quite interesting. It allows for WYSIWYG editing of UI elements, which could partially solve the fine-tuning problem I mentioned. I tried it, but it's still quite basic, only allowing changes to text content, font size, margins, etc. It doesn't support features like drag-and-drop. The long-term vision for this is compelling—it could even take on Figma—but the technical difficulty seems immense. (It reminds me that we don't even have a truly good visual editor for Mermaid diagrams yet.)

YouWare: A Radical Experiment in User-Generated Software

The truly exciting thing about AI coding is its demonstration of the ability to "dispatch compute with natural language." This empowers ordinary people to use code as a tool to solve their own previously unmet needs. An era of User-Generated Software (UGS) is dawning.

Among all the products, YouWare seems to be a platform built precisely for this purpose, making UGS its sole mission.

Is turning AI coding into a content community the right move?

Initially, I was cautiously pessimistic about YouWare.

It felt like they were trying to force the UGC (User-Generated Content) playbook (community, traffic, platform) onto UGS. If they're building a new content platform, they're competing for attention with TikTok and Instagram, but it doesn't seem as "scrollable." The demand for personalized entertainment has been thoroughly met by short videos. (…or has it? As I say this, I suddenly feel that short videos aren't always that great, and I often struggle to find games that match my preferences.)

My initial thought was: the potential of UGS lies in satisfying the massive long tail of unmet tool-based needs. Users don't lack motivation; they lack the ability. If they are solving their own pain points, they will leave after the job is done. They won't necessarily have the desire to share or distribute their creations (or posting on Twitter/Instagram is enough), and they certainly won't be "scrolling" through a tool website for fun.

YouWare believes that many people don't know what they can create, so a platform is needed to spark their imagination and creativity. Social elements play the role of inspiration here.

Platforms like v0 and Lovable, while claiming to be accessible to beginners and having some community features, still show users the code, pop up build errors, and ask you to connect to Supabase. Their assumed user is still a "professional" with some technical background (like a product manager or designer). For example: "Lovable provides product managers, designers, and engineers with a shared workspace to build high-fidelity apps, collaborate effectively, and streamline the path to production-ready code."

YouWare's radical approach is that it completely hides the code from the user. Its target non-coder is the general public.

This is a bit like how Instagram limited the length of text in posts. By imposing a constraint, it maximized usability for its target audience. For someone who knows nothing about technology, seeing a build error is a dead end. In YouWare, that dead end is hidden.

Regarding the difference between tool needs and entertainment needs, Instagram can also be seen as a tool for users to document their lives, and its popularity is largely due to its "usefulness."

After trying YouWare myself (my creations), I noticed some interesting things:

-

It's genuinely a bit addictive (and the free credits are very important). For example, if I have a random idea, I'm tempted to just throw it on there and see what happens. If I were using another platform for a serious project, I'd have to think it through more carefully. (My mental model includes the cost of debugging, etc., because I want something that actually works. In terms of mental burden, YouWare < Lovable < Cursor, but the utility is probably the reverse). This feeling is very similar to using Cursor's background agent—"Let's just run it and see, what's there to lose?"

-

It truly hides the code details, including failures. When I tried Lovable, the initial generation often resulted in an error (though it was fixed with a click), whereas YouWare never did.

-

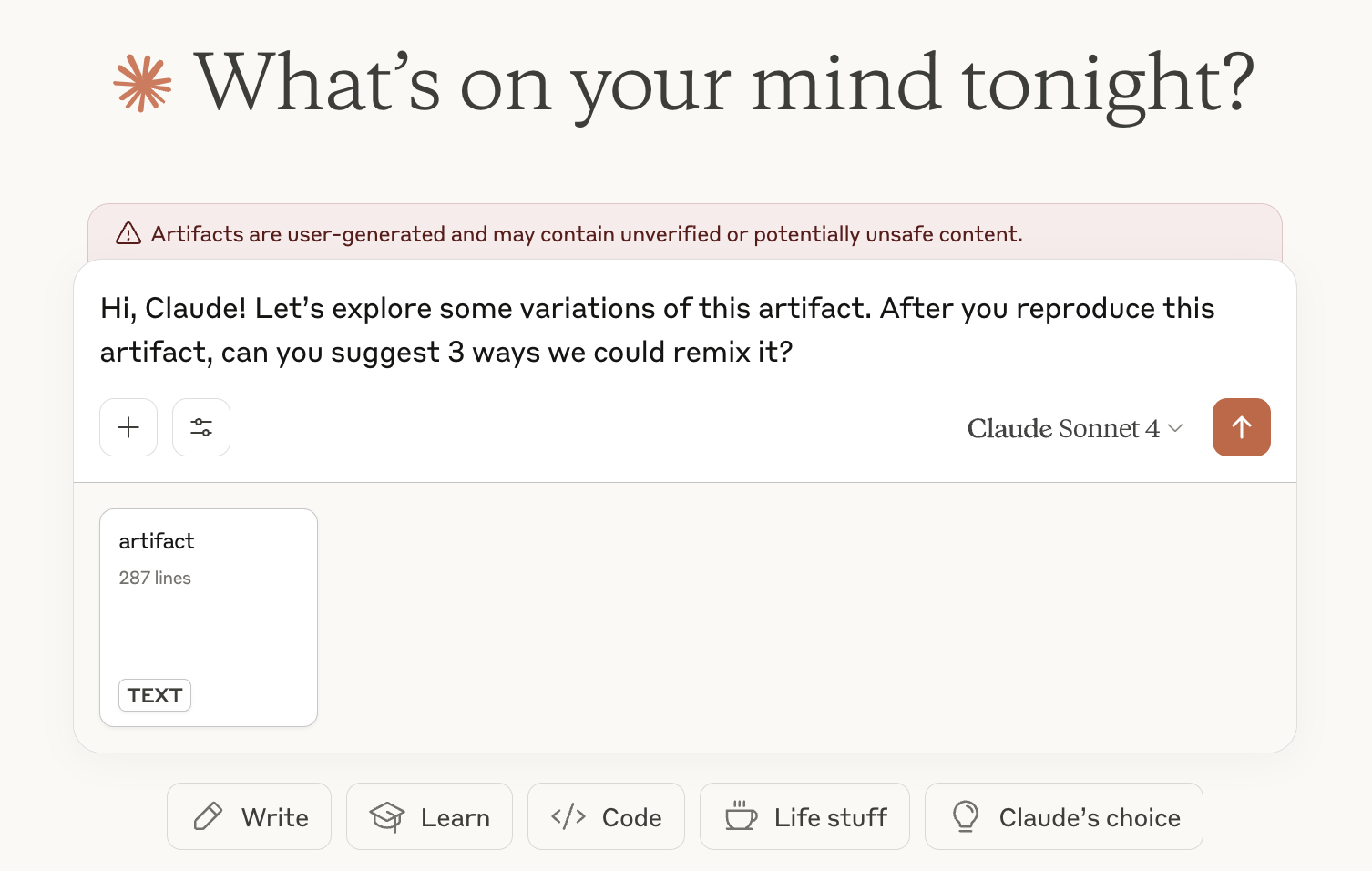

It encourages "play." YouWare's Remix and Boost features are also interesting (regardless of their effectiveness for now). They align well with the premise that "users don't know what they want to build," encouraging exploration and re-creation.

-

But then I realized many platforms have this now, even Claude's Artifacts have a similar feature, and it's surprisingly polished.

-

A Bunch of Scattered Thoughts on YouWare

-

Who are Vibe Coders? The UGC era gave rise to professional "creators." Today's "vibe coders" are somewhat similar. But content creators' income mainly comes from traffic and brand deals, whereas vibe coders are closer to indie developers. They want to build their own products and make money by selling software or subscriptions. Selling software ultimately depends on solving real needs and promoting it on various platforms, not waiting for someone to stumble upon you on a UGS platform (e.g., you'd promote on Instagram, not wait for someone to find you on GitHub). …Thinking about this, a wild idea popped into my head: if you were really going to do this, shouldn't you build an OnlyFans for vibe coders, rather than a YouTube/Instagram? 🤣

- Code does have entertainment value (there's a thing called creative coding)… but again, entertainment demand competes for attention. A niche use case is turning articles into interactive websites for educational purposes, like these:

-

Power Users vs. Novice Users: The needs of these two groups are contradictory, and it's hard for one platform to satisfy both. YouWare has clearly chosen the latter.

-

Limitations of the Output Format: Why are the final outputs of these coding platforms (including Devin, Lovable, etc.) mostly websites? For many small utility needs, a command-line tool or a desktop app might be more direct and efficient. Of course, from a UX perspective, websites are the most user-friendly for the general public.

- Cost Issues:

- As a content platform, there are significant compliance risks and costs. But maybe it's not that hard, given that even DeepSeek can operate in China.

- The cost of hosting websites. Different types of websites may have different computational needs, and popular projects might require dynamic scaling.

- The massive compute cost of agents. Unlike UGC, where the platform has little cost when users create content, UGS is different. Compared to Amp, which says its optimization goal is maximum utility, YouWare's accounting is much more complex. There's a huge trade-off between generation quality and cost.

- This leads to a core question: if it encourages user creation, what is its business model? If it follows the traditional traffic-and-ads model of content platforms, given the huge costs, the profit ceiling is likely not high.

- Should it optimize for specific scenarios?

- For example, maybe half the users on the platform are using it to write reports. But that's really a DeepResearch-type function, and the results in YouWare would be mediocre. Manus/Flowith would probably optimize for this (Manus recently even specialized in a slides feature, which left me a bit speechless—so much for a general-purpose agent).

- Data-driven platform evolution?

- I was initially puzzled why YouWare (and Manus, etc.) would heavily invest in traffic acquisition and promotion while their capabilities were still incomplete, instead of polishing the product first. Perhaps they have secured enough funding and are in a rush to expand.

- But launching before the product is mature can help them understand what users actually want to build, and then optimize accordingly. I may have underestimated the role of social interaction in sparking user creativity. This could be like an evolutionary algorithm, or the idea that "greatness cannot be planned": let users explore freely, and you might see unexpected innovations emerge. The YouWare team's background at ByteDance suggests they will likely follow a data-driven decision-making process, letting user behavior guide the platform's evolution. Perhaps they will stumble upon a breakthrough along the way.

The Future of YouWare

I believe every company has its DNA. The founder of YouWare, a former PM from ByteDance's CapCut team, is perhaps the only one who could have come up with something like this.

While many of the things I analyzed above might see Lovable moving towards YouWare's direction (hiding more code) or YouWare moving towards a standard agent platform (increasing utility), I'm excited to see the outcome. I think YouWare's current form is not its final form. At the same time, I increasingly find YouWare's starting point fascinating, and it might just create something different. This team might understand creation, platforms, and consumers better than the coding folks, and understand AI coding better than the creator folks.

YouWare's goal isn't to maximize utility, but to unleash the creativity of ordinary people. Of course, the utility has to be at least good enough.

A harsh question is: as more and more people learn to use Cursor, will it eat up the market for these "dummy" tools? Perhaps it will be like how professional photographers with cameras and ordinary people with phone cameras coexist; programmers and vibe coders will coexist. Another thought I've been having recently is that current AI is exacerbating the Matthew effect (perhaps starting with the \$200 subscriptions). The gap between those who know how to use AI well and can afford it (I've seen people burn hundreds of dollars a day on Cursor) and the average person will widen. Will those less inclined to think critically, who can't articulate their needs clearly, be "left behind"? That future is too cruel for me to imagine, and I'd rather join the resistance against that trend. From this perspective, I find attempts like YouWare, dedicated to serving the broad public, very valuable.

Of course, while YouWare is full of ideas, whether that vision can be successfully translated into a viable product and achieve commercial success remains uncertain.

Big Picture: Industry Landscape & Technical Directions

After examining the players at the table one by one, let's take a step back and look at the entire AI coding landscape.

Market Segmentation

AI coding can be broken down into several sub-fields. A single product might span multiple areas:

- AI-assisted Coding: Represented by Cursor and GitHub Copilot, these are "enhancers" for existing development workflows, aimed at making professional developers faster and more productive.

- End-to-end Agents: Represented by Devin, Claude Code, and Amp, their goal is to become "junior engineers" who can complete tasks independently, elevating developers from executors to task assigners and reviewers. Agents can also be collaborators, especially CLI-based agents like Claude Code, with whom I can either pair program or delegate work. A thought leader in a video predicted that by Q3 2025, the consensus in Silicon Valley will be that Agents can reach or even replace mid-level software engineers. The comments section was mostly skeptical. My take is that Agents might not "replace" them entirely, but they are very likely to become powerful "partners" for mid-level engineers. Understood from this angle, I think the prediction is quite reasonable.

- Vibe Coding / UGS: Represented by v0 and YouWare, these tools attempt to give the power of code to non-developers, allowing them to create applications and tools through natural language. One is more geared towards "product prototyping," while the other takes a more radical step towards a "content community."

The Awkward "Half-Baked" State of Affairs

We have to admit a reality: Agents are still a "half-baked" product. Their performance is not yet good enough to deliver a perfect result end-to-end, and sometimes it's less hassle to just do it ourselves (like manually adjusting a button).

But we can also clearly see the evolutionary path of agents: from manually copying and pasting in ChatGPT, to single-turn conversations in an IDE, to today's Cursor Background Agent and Claude Code. The length of time an agent can work independently is increasing, and the quantity and quality of its work are improving. This is an irreversible trend.

Perhaps we should adopt a different mindset: think of it as an outsourced contractor. You assign it a task, let it work for a while, and then you come in to review and give feedback, rather than expecting it to get everything right in one go. This is no different from how we collaborate with human contractors (who are, in a sense, "Agents").

The Curse of Cost, and the Bet on Models

At the same time, Agents are very expensive. This not only discourages users from large-scale adoption but also puts agent application companies in a dilemma: should they continue to pursue performance at any cost, or should they turn to various "tricks" and "polishing" to reduce costs and improve efficiency? But there is a trade-off between performance and cost. I don't know if it's possible to have both, for example, by having one part of the team focus on performance and another on cost optimization. If cost control is completely ignored, the high price might scare away users. But are AI Agent companies really in such a hurry to acquire customers? Maybe not.

There's a bigger variable at play here: if the upstream LLM providers drastically cut their prices, all the previous efforts in cost optimization, like painstakingly optimizing by 30-50%, could be rendered "wasted effort" by external factors. Of course, there's also the possibility that the original providers' optimizations are ineffective, or that they decide to develop their own Agent business. Therefore, for AI Agent startups, their decisions are filled with elements of a "gamble."

What Capabilities Does an Agent Need? How to Build a Coding Agent?

From the explorations of various products, we can glimpse the capabilities a good Agent needs:

- Memory/Knowledge Base: For example, the ability to automatically learn from

cursor.rulefiles (Devin/Manus already have this). - Long Context Capability: Indexing & RAG?

- I'm a bit skeptical about the effectiveness of this. Now that we're in the Agent era, the agent can just

grepthe code to find context. This is very similar to my own development process. It's still heavily reliant on string searching, which isn't a very smart method. Butgrepis only useful when you know what to change. Vague questions like "how does xxx work?" are a different story. - But testing long context capability is very difficult; you need to use it very deeply to know its true level. I haven't gotten a feel for it yet.

- I'm a bit skeptical about the effectiveness of this. Now that we're in the Agent era, the agent can just

-

Task Management Capability: I used to think an external to-do list was essential, but now it seems Claude is starting to internalize this capability – the model may output things like "Let me solve the problems one by one: 1. … 2. … 3. …" (though my gut feeling is that an external one is still better?).

- Proactive Communication & Interaction: A good Agent shouldn't just do what you say. It should be like a good contractor: it should ask clarifying questions, confirm intent, and assess risks (like Devin's "confidence rating"). For example, if you say "I need to make a PowerPoint," it should ask if you have existing materials or textbook resources to provide. Deep research products are also doing a good job with this.

On that note, does building a good coding agent require you to be a great user of coding agents yourself?

Final Thoughts: Our Relationship with AI

The concepts of "natural language dispatching compute" and "User-Generated Software" may have somehow become an industry consensus, but their specific implementation is far from agreed upon.

After all this talk, let's bring it back to ourselves.

How should the average person choose?

In general, all tools are currently in a state of "still early, but already useful (if used correctly)." They perform well on small, simple tasks or for generating demos, but in complex scenarios, they heavily test the user's "craft."

This "craft" includes both prompt engineering skills and an understanding of code and how agents work. "Knowing the boundaries of AI's capabilities" is also a bit of a cliché by now. Therefore, the people who will use Agents best in the future will likely still be professionals. It's like professional photographers versus casual phone photographers: the tools blur the lines between professions (e.g., engineers can do design, PMs can write demos), but ultimately, they raise the ceiling for experts.

Agents are likely something that gets better with use. Exploring best practices within a team, accumulating prompt techniques and a knowledge base—this is an investment in itself.

But I also often wonder if studying all this is futile. When model capabilities reach a certain singularity, we can just embrace the final form, and all the intermediate explorations and usage experiences will become obsolete. This might be true. There's no point in arguing further, and I'm no longer going to force anyone to use AI. But I just can't help playing with it. It's fun! 😁🤪

When the power to generate becomes infinite, what should we generate with it?

A deeper question: What does the development of AI really have to do with me? It's like how I don't read many research papers; they feel distant. Although ChatGPT has made it much easier for me to learn anything—I'm constantly discussing things with it—I find myself more tired. Do I really need to know all this stuff?

The development of Coding Agents will allow me to write more and more code. Should I build all those things? When the power to generate becomes infinite, what should we actually generate with it?

Products like YouWare might be one answer.

Or perhaps, this is a non-existent problem, like asking what we should do after achieving controlled nuclear fusion. Will everyone get to pilot a Gundam?